Thyroid Gland Physical Examination Signs

Examination of the thyroid gland. Illustration of the optimal position of the palms and use of the 2nd, 3rd and 4th digits in palpating the thyroid gland in the low anterior neck.

Our approach involves sequentially inspecting, palpating, percussing (where relevant), and auscultating the thyroid.

Inspection of the thyroid gland

- A visible anterior neck mass, which is mobile on deglutition, implies an enlarged gland. Offer the patient a glass of water to drink. The normal thyroid gland cannot be visualized on inspection.

- Positive Pemberton’s sign is suggestive of significant retrosternal extension of a goiter.

Palpation

- Optimal positioning of the neck will facilitate palpation of the gland. The patient’s neck should be in a relaxed position, which prevents extensive nuchal extension or flexion. The sternocleidomastoid muscle should not be under tension, and there should be adequate room between the chin and the sternum to allow proper positioning of the hands.

- Sequentially palpate each thyroid lobe and isthmus. Occasionally there might be an accessory extension of the isthmus – the pyramidal lobe. Check for the consistency of the gland. Avoid deep palpation if the gland is tender, as might occur in De Quervain’s thyroiditis. The normal thyroid has a mild firm consistency. The overlying skin is usually freely mobile over it. If the gland is attached to overlying skin, it might be suggestive of either a malignancy or Riedel’s thyroiditis.

- Attempt to feel for any discrete thyroid nodule. These are best appreciated using the pulp of your examining fingers (2nd, 3rd, and 4th digits)

- Ask the patient to swallow during palpation and check for any retrosternal extension of the thyroid gland.

- Grade thyromegaly with the WHO classification system (see section 2.3.2)

- Palpate all regional lymph node groups (I to VI)

Percussion

- Percussion of the sternal manubrium may be required in patients with a suspected retrosternal goiter. The percussion note will be dull. This step is seldom warranted, especially if there is no palpable thyroid tissue extending below the proximal portion of the manubrium (thoracic aperture).

Auscultation

- In patients with hyperdynamic circulation, as might occur in overt Graves disease, a bruit may be appreciated over the superior poles of the thyroid in the vicinity of the superior thyroid arteries.

Hashimoto’s Disease

Queen-Anne’s sign

This eponymous medical sign is named after Anne of Denmark, due to her truncated lateral eyebrows, which was depicted in a portrait by Paul Van Somer. Facial and body hair tends to be dry, thin, and brittle in hypothyroidism.

Hair loss over the lateral third of the eyebrow is a recognized sign of hypothyroidism.

Bradycardia

Hypothyroidism is a known cause of bradycardia and significant bradyarrhythmias such as high grade atrioventricular (AV) block. A recent retrospective study involving 668 subjects, reported the need for permanent pacemaker insertions in some patients who presented with high-grade AV block, even after resolution of hypothyroidism.

Pericardial and pleural effusions

The incidence of pericardial effusions ranges between 3-6%, in mainly advanced stages of hypothyroidism. Pericardial effusions in mild hypothyroidism are, however, rare. Pleural effusion can be diagnosed by eliciting a “stony dull” percussion note and reduced tactile vocal fremitus over the lung zones.

Distant heart sounds, hypotension pulsus paradoxus, and jugular venous distension may be observed in significant pericardial effusions.

Dry skin

Dry skin (xerosis) is a cardinal skin manifestation of hypothyroidism. Xerosis is the most frequent cutaneous manifestation of hypothyroidism, with a prevalence greater than 65%. In a small study designed to assess the predictive value of the physical examination in suggesting a diagnosis of hypothyroidism, rough, dry skin had a reported positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of +2.3 in diagnosing hypothyroidism.

Other cutaneous changes seen in clinically significant hypothyroidism include lymphedema and myxedema.

Table 1. Other skin manifestations of hypothyroidism

| Lesion | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Lymphedema (hands, face, and eyelids) | Accumulation of hydrophilic mucopolysaccharides in the interstitial space impairs lymphatic drainage |

| Myxedema | Deposition of mucopolysaccharides in the skin |

Adapted from Ai et al. (2003) Autoimmune thyroid diseases: Etiology, pathogenesis, and dermatologic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 48:641–662

Macroglossia

Macroglossia is a rare sign of hypothyroidism and is described as protrusion of the tongue beyond the teeth during a state of normal relaxation of the tongue musculature.

Hyporeflexia

Hyporeflexia in hypothyroidism classically presents as a reduced relaxation phase of deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). This has been eponymously labeled as the “Woltman sign of myxedema”.

It is best elicited at the ankle joint with the patient in a seated position and the lower extremities in a dependent position. This allows an accurate assessment of the relaxation phase of the reflex since relaxation will be occurring against gravity.

Proximal myopathy

Myopathy presents with proximal muscle weakness involving the pelvic or shoulder girdle musculature. Clinically identifiable neuromuscular dysfunction had a prevalence of approximately 40% in a prospective cohort study assessing neuromuscular dysfunction in patients with hypothyroidism.

Hoffman syndrome, a form of hypothyroid-related muscular dysfunction, is described as a triad of muscle weakness, hyporeflexia, and muscular hypertrophy.

Galactorrhea

Patients may present with galactorrhea, although spontaneous or expressible galactorrhea is a rare finding in primary hypothyroidism.

Graves Disease

Thyroid eye disease

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is the most common extra-thyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease. TED can present with a myriad of ocular signs, including photophobia, proptosis, or conjunctival injection. Other signs suggestive of TED include lid lag, globe lag, lid retraction, and even, in some severe cases, evidence of optic neuropathy.

Table 2. Selected eponymous thyroid eye signs in Graves’ disease

| Eye sign | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Dalrymple’s sign | Lid retraction involving the upper eyelid |

| Collier’s sign | Lid retraction involving the lower eyelid |

| Von Grafe’s sign | Lagging of the upper eyelid upon downward gaze |

| Stellwag’s sign | Infrequent blinking of the eyelids |

| Rosenbach’s sign | Tremors of the eyelids upon closure |

| Gifford sign | A difficulty with eversion of the upper eyelids |

| Jellinek sign | Hyperpigmentation of the upper eyelids |

| Sainton sign | Nystagmus on the voluntary horizontal movement of the eyes |

| Ballet sign | Paresis of extraocular muscles |

| Enroth sign | Periorbital edema |

| Griffith’s sign | Lid lag involving the lower eyelid on upward gaze |

Pretibial myxedema

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous manifestation of Graves’ disease and can appear as non-pitting edema, plaque-like, or nodular lesions. In severe cases, it may appear like the lymphedema associated with elephantiasis. The nodular variant occurs in fewer than 10% of subjects and has been reported to mimic the characteristic lesions of erythema nodosum. PM can recur several years after definitive treatment of Graves’ disease, i.e., surgery or radioactive iodine ablation.

Other cutaneous manifestations of hyperthyroidism include urticaria, telangiectasia, erythema, and warm skin.

Table 3. Other skin manifestations of hyperthyroidism

| Lesion | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Warm and moist skin | Vasodilation of cutaneous vessels |

| Palmar erythema | Vasodilation of cutaneous vessels |

| Urticaria | Binding of anti-TPO Immunoglobulin E antibodies to receptors on the surface of mast cells leads to their activation and degranulation |

| Telangiectasia | Increased dermal blood flow and a possible immune-mediated process have been proposed |

Thyroid acropachy

Thyroid acropachy (TA) is characterized by digital clubbing involving the upper and lower extremity digits. It has a strong association with thyroid eye disease and may in some instances, herald a diagnosis of Graves’ disease

What might be seen on a plain radiograph of an involved extremity, for patients with TA? A periosteal reaction involving bones of the hand or feet might be seen on a plain radiograph. TA presents with a clinical triad of periosteal reaction, swelling of the hands or feet, and clubbing of the digits

Onycholysis

Onycholysis has eponymously been referred to as “Plummer’s nails.” Dr. Henry Plummer of Mayo Clinic described various characteristic features of dystrophic nails in hyperthyroidism, including the unique “scoop shovel” appearance and flattening of the fingernails. Plummer’s nails present as a separation of the distal aspect of the nail from its underlying nail bed. It is an inconsistent physical finding and occurs in approximately 5% of patients with hyperthyroidism.

Periodic paralysis

A form of periodic paralysis known as thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) occurs in patients with Graves’ disease and may present with either mild muscle weakness or overt flaccid paresis. TPP occurs most often in people of East Asian descent but has been described in other ethnicities.

Thyroid bruit and thrill

Bruits auscultated over the superior thyroid arteries are detectable in up to 85% of patients with symptomatic hyperthyroidism. They are continuous (throughout the cardiac cycle) and are accentuated in the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle. The auscultatory findings of a thyroid bruit are different from those of carotid bruits or radiating cardiac murmurs to the neck. The bruit associated with carotid artery disease, for example, tends to occur only in the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle.

It is worthy to note that the presence of a thyroid bruit on the clinical exam is pathognomonic for an autonomously hyperfunctioning gland (Graves disease). This clinical finding effectively rules out thyroiditis in patients with biochemical hyperthyroidism.

Tachycardia

Patients with hyperthyroidism classically have tachycardia, with more than 90% having a resting heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute. Atrial fibrillation, a cause of tachycardia, is, however, less frequent in Graves’ disease. Indeed, elderly patients with “apathetic hyperthyroidism” are more likely to have atrial fibrillation than younger patients.

An irregularly irregular peripheral pulse is a hallmark of atrial fibrillation on the clinical exam.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia is a known clinical manifestation of thyrotoxicosis but is seldom a presenting feature of the disease. Gynecomastia is usually reversible after the control of hyperthyroidism. It presents as palpable subareolar tissue and should be differentiated from pseudogynecomastia (lipomastia), which is a generalized accumulation of fat in male breasts.

Lymphadenopathy

Perithyroidal lymphadenopathy is a reported finding in benign thyroid disease. Up to a third of patients with Graves’ disease in a recent cross-sectional study were noted to have clinically discernible perithyroidal lymph node enlargement.

Change in body composition (weight loss)

Patients with uncontrolled thyrotoxicosis present with unintentional weight loss in the setting of hyperphagia. Loss of body fat and muscle bulk may be discernible on the routine clinical examination.

Euthyroid Goiter with Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Pemberton’s sign

This sign is eponymously named after Dr. Hugh Pemberton, who described this classic physical finding in a letter published in Lancet in 1946 titled “sign of a submerged goitre.” He explained the method of eliciting the sign, expected clinical findings, and also proposed a mechanism for the physical finding.

The sign is elicited by instructing the patient to lift their arms such that the arms touch both sides of the head. The patient is then instructed to hold their arms in that position until facial congestion or erythema is noticed.

Other Compressive signs (superior vena cava syndrome, phrenic nerve paralysis)

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome can occur in patients with large goiters. There are multiple case reports of mediastinal goiters leading to SVC syndrome. A goiter may sometimes not be palpable on the physical exam due to its ectopic position in the mediastinum.

Clinically significant dyspnea due to either unilateral or bilateral phrenic nerve compression by large retrosternal goiters has been reported. In a recent large series of 50 retrosternal goiters, nerve compression syndromes were second only to tracheal compression in terms of clinically significant complications.

Table 4. Modified World Health Organization (WHO) classification for the clinical evaluation of a goiter

| Grade | Examination findings |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Goiter not visible or palpable |

| Grade 1 | Goiter not visible in the normal position of the neck but is palpable. The thyroidal mass should be palpable on deglutition |

| Grade 2 | Visible and palpable goiter |

Resistance to thyroid hormone

Goiter

Goiter is frequent in patients with thyroid hormone resistance syndromes, a state of differential tissue insensitivity to circulating thyroid hormone, with a reported prevalence of 66-95%.

Short Stature

In a prospective study at the National Institutes of Health, including 104 patients with thyroid hormone resistance, 18% had short stature.

Does TSH hypersecretion due to thyroid hormone resistance lead to thyroid adenomas or cancer?

TSH hypersecretion causes mild enlargement of the thyroid gland, but there is no evidence that it increases the risk of either adenoma or malignancy.

What is the eponymous name for thyroid hormone resistance syndromes?

The first case of thyroid hormone resistance was described in 1967 by Dr. Samuel Refetoff and his colleagues. “Refetoff syndrome” was first used in a published case report from Japan. Subsequent case reports have since used this eponymous term.

Medullary Thyroid Cancer

Facial flushing and other clinical features of neuroendocrine origin.

Patients with medullary thyroid cancer can present with facial flushing. It is described as a “dry flush” due to the absence of associated cutaneous sweating, in contrast to the “wet flush” of menopause.

Cervical mass

The most frequent clinical finding in MTC is the presence of a mass or nodule in the cervical region, with a reported prevalence of 35% to 50%. Neck findings could be due to cervical lymph node involvement or compressive neck symptoms due to an enlarged thyroid nodule.

Which endocrine conditions present with MTC?

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and 2B

- Familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (FMTC)

- Sporadic MTC occurs much later in life between 40 and 60 years of age. Hereditary MTC encompasses MEN type 2 syndromes and FMTC, and tends to occur much earlier in life compared to sporadic MTC.

At what age and in which specific inherited endocrinopathies should prophylactic total thyroidectomy be performed?

Patients should have a total thyroidectomy by 5 years of age if they have MEN2A with germline mutation involving the RET codon at position 634 or MEN2B.

Pituitary Gland Physical Examination Signs

Cushings Disease

Proximal myopathy

Harvey Cushing reported muscle weakness as a cardinal finding in his original description of Cushing’s disease. Proximal myopathy is an essential clinical clue in patients with overt hypercortisolism, with variable rates of prevalence ranging from 40 to 70% in retrospective studies.

Proximal muscle weakness associated with Cushing’s disease presents as an inability to either climb stairs or get up from a seated position without assistance. Loss of handgrip strength is also a known physical manifestation of Cushing’s disease, although pelvic girdle muscles are more likely to be involved than pectoral girdle and upper limb muscles.

Fat maldistribution

Visceral adiposity in the setting of endogenous hypercortisolism has been referred to as “Cushing’s disease of the omentum”. Abnormal fat distribution can also be disproportionately higher over the dorsocervical, supraclavicular, or temporal regions compared to the extremities.

Striae and skin atrophy

Striae observed in Cushing’s disease tend to be broad and violaceous, in contrast to the pale-colored thin striae associated with obesity. In darker-skinned individuals, striae may, however, not appear purple. Striae are typically distributed over the flanks, lower abdomen, upper thighs, and buttocks.

Skin atrophy can be assessed clinically by measuring skinfold thickness with a skin caliper. Bedside assessment of skinfold thickness has been validated as an essential clinical tool in the evaluation of hypercortisolism. An improvised simple electrocardiographic caliper with its sharp edges blunted can be used to assess skinfold thickness over the proximal phalanx of the middle finger of the nondominant hand.

A skinfold thickness of 1.5mm or lower is predictive of hypercortisolemia when comparing patients with Cushing’s disease to controls without endogenous hypercortisolism.

In a recent paper, a skin thickness threshold of < 2mm was reported as being consistent with clinically significant thin skin. The positive likelihood ratio (+LR) for predicting endogenous hypercortisolism in patients with skin thickness less than 2mm was estimated as 116.

Facial plethora

Facial plethora is a common clinical finding in patients with hypercortisolism and is highly predictive of Cushing’s disease. Of note, the other positive discriminatory findings of endogenous hypercortisolism include easy bruising, proximal myopathy, and purplish striae >1cm.

Hirsutism

Hirsutism, a sign of androgen excess, is more common in the setting of adrenal carcinoma compared to Cushing’s disease. Nonetheless, hirsutism in the right clinical context can be suggestive of endogenous hypercortisolemia. Hirsutism presents in females as excessive terminal, pigmented hair growth, distributed in a classic male-pattern.

Associated endocrinopathies/differentials of hirsutism

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH, both classical and nonclassical)

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome(PCOS),

- Cushing’s disease,

- Acromegaly

- Insulin resistance, Hyperandrogenism Insulin Resistance Acanthosis Nigricans (HAIR-AN syndrome) and virilizing adrenal, ovarian, or ectopic tumors.

Hypertension

80% of patients with Cushing’s syndrome have hypertension. Of note, Cushing’s-specific hypertension and primary hypertension may co-exist in the same patient.

Fragility fractures

Endogenous hypercortisolism increases the risk of low bone mineral density in a manner akin to exogenous glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP). Unlike exogenous GIOP, there is very little published literature on the prevalence of osteoporosis related-fractures in patients with Cushing’s syndrome.

Hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation of the skin can occur in Cushing’s disease, although it is more common in patients with ectopic ACTH production. For patients with Cushing’s disease, hyperpigmentation is common in those with persistent pituitary disease after bilateral adrenalectomy, i.e., Nelson’s syndrome. Hyperpigmentation is usually evident in scars, buccal mucosa, conjunctivae, and sun-exposed areas.

Acromegaly

Acanthosis nigricans

Patients with acromegaly exhibit some signs of insulin resistance. Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a cardinal dermatologic feature of insulin resistance and appears as a hyperpigmented, velvety skin lesion that has a predilection for flexural areas such as the neck, groin, and antecubital fossa.

Frontal bossing and prognathism

Frontal bossing and prognathism are cardinal craniofacial manifestations of acromegaly. Other signs include dental malocclusion and nasal bone hypertrophy. In a study involving 29 acromegalics, the investigators assessed for any improvement in craniofacial skeletal deformities after curative tumor resection.

Prespecified skull measurements did not differ significantly when the pre- and postsurgical dimensions were compared on serial Magnetic resonance images (MRIs). These physical findings, unfortunately, will persist even after curative operative management of acromegaly, based on the results of this study.

Acrochordons and other skin manifestations

Various cutaneous changes occur in acromegaly, including acrochordons (skin tags) and psoriasis. Acrochordons, a sign of excessive soft tissue proliferation, may also point to the presence of synchronous colonic polyposis.

Three or more skin tags in patients with a disease duration of 10 years are associated with a high pre-test probability for concomitant colonic polyposis. Other skin and soft tissue manifestations include large lips or noses, oily skin, and hyperhidrosis.

Tinel Sign (Carpal tunnel syndrome)

Nerve entrapment syndromes like Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and ulnar nerve neuropathy occur in acromegalics. CTS has a prevalence of 20 to 64% in patients with acromegaly. Positive Tinel’s sign is the presence of reproducible median nerve compressive symptoms (tingling sensation involving the first three and a half digits) upon tapping the location of the median nerve, just proximal to the wrist joint. Tinel’s sign has positive and negative predictive values of 88% and 76%, respectively.

Hypertension

Hypertension increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with acromegaly, with an estimated prevalence of 33-46%

Prolactinoma

Hypogonadism

Prolactinomas usually present with hypogonadal symptoms in men. These include erectile dysfunction, infertility, and decreased libido. Premenopausal women may have either oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea.

Gynecomastia and Galactorrhea

Galactorrhea is defined as the secretion of a milky fluid from the breast, either spontaneously or with manual expression, in the absence of gestation. Galactorrhea occurs in both men and women, although it tends to be more prevalent in the latter. Gynecomastia is the benign growth of male breast glandular tissue.

Bitemporal hemianopsia

Bitemporal hemianopsia presents as a loss of peripheral vision. The presence of this peripheral scotoma may impact a patient’s functional status negatively, including the ability to drive a motor vehicle. It is best measured by conventional perimetry, although a simple bedside visual field confrontation test can be helpful in the initial assessment.

The classic presentation of bitemporal hemianopsia is rare in patients with visual field defects due to a pituitary macroadenoma.

In a recent retrospective study comparing pituitary MRI findings with formal visual field records, the authors reported other visual field defects as being more likely even in the presence of significant optic chiasmal compression, defined as a chiasmal displacement greater than 3mm. Interestingly, a single patient out of a cohort of 115 had the classic presentation of bitemporal hemianopsia, despite the evidence of chiasmal compression. These findings are indeed inconsistent with the long-held view of bitemporal hemianopsia being the likely visual field defect in the setting of chiasmal compression.

Growth Hormone Insensitivity (Laron-type dwarfism)

Short Stature

Laron-type dwarfism is the most severe form of growth hormone insensitivity and was first described in 1966. Children born with Laron dwarfism have a growth velocity of less than 50% of their predicted rate. Patients are of short stature with a final height being -4 to -8 standard deviations below the normal for their age and gender.

Obesity

Obesity in subjects with Laron-dwarfism worsens progressively with age. Patients have a higher proportion of body fat compared to age and gender-matched healthy controls. Dr. Zvi Laron and colleagues reported severe obesity as a cardinal clinical sign in both children and adults with Laron-dwarfism.

Small genitalia

There is a delayed but eventual achievement of full sexual maturity. The male testis reaches a final adult size of 5-9ml, which is lower than that of healthy subjects[104]; nonetheless, both sexes can still achieve fertility in adulthood.

Central Diabetes Insipidus

Dehydration due to polyuria and polydipsia

Patients with central diabetes insipidus present with hypotonic polyuria and polydipsia. Excessive free water loss leads to clinical signs suggestive of dehydration

Adrenal Gland Physical Examination Signs

Addison’s disease

Postural Hypotension

Arterial blood pressure decreases in patients with primary adrenocortical insufficiency. Orthostatic hypotension can be elicited at the bedside by confirming a postural drop in blood pressure in changing from a supine to a semi-recumbent position or standing position.

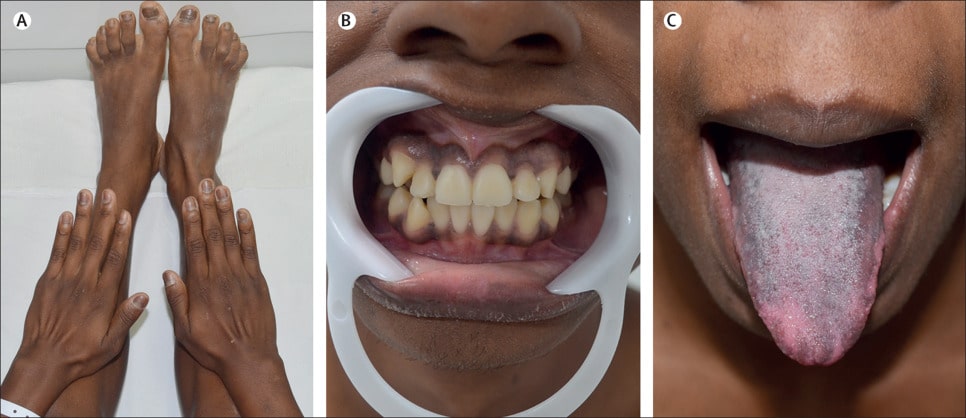

Source : https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31680-9

Source : https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31680-9Hyperpigmentation

Addison’s disease presents with a classic dermatologic feature of hyperpigmentation involving sun-exposed areas, areas of prior trauma, palmar creases, oral mucosa, conjunctivae, and the nails (dark longitudinal ridges referred to as melanonychia).

What are the other clinical features of Addison’s disease?

Table 5. Clinical features grouped by the underlying mechanism

| Clinical features | Underlying mechanism |

|---|---|

| Postural dizziness, hypotension, salt craving, and weight loss | Mineralocorticoid insufficiency |

| Confusion, pallor, and diaphoresis | Hypocortisolemia induced hypoglycemia |

| Nausea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort | The pathophysiology is uncertain |

| Loss of androgen-dependent hair (adolescents, females) and reduced libido | Androgen deficiency |

| Vitiligo | Autoimmune-mediated destruction of melanocytes |

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Hypertension

Primary hyperaldosteronism happens to be the most common cause of secondary hypertension, with a reported prevalence of 5-10% amongst all hypertensive patients and as high as 20% in those with resistant hypertension.

Muscle weakness

Significant muscle weakness can occur in patients with primary hyperaldosteronism. There are a few case reports of myopathy as the presenting feature of Conn’s syndrome.

Atrial fibrillation

An association of atrial fibrillation with hyperaldosteronism is widely accepted, there is, however, a paucity of prospective study data on the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in subjects with hyperaldosteronism.

Patients with primary aldosteronism are at a 12 fold risk of developing atrial fibrillation compared to patients with essential hypertension. An irregularly irregular pulse rate and rhythm is the classic clinical finding in atrial fibrillation.

Dehydration

Patients with primary hyperaldosteronism can present with hypotonic polyuria and polydipsia.

Questions you might be asked on clinical rounds

What clinical features should prompt a clinician to screen a patient for primary hyperaldosteronism?

Screening recommendations for hyperaldosteronism

| Endocrine Society screening recommendations |

| · Blood pressure above 150/100 mmHg; should be measured on three occasions on separate days |

| · Uncontrolled blood pressure on three or more antihypertensives, including a diuretic ∆ |

| · Controlled blood pressure requiring four or more antihypertensive agents. ∆ |

| · Hypertension in the setting of sleep apnea or adrenal incidentaloma |

| · Hypertension with a family history of early-onset hypertension or stroke at < 40years of age |

| · First-degree hypertensive relatives of patients with primary hyperaldosteronism |

∆ Suggestive of resistant hypertension.

Adapted from Funder et al. (2016) The Management of Primary Aldosteronism: Case Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101:1889–1916

What are the causes of pseudohyperaldosteronism

These are endocrine conditions that present with some of the clinical features of primary hyperaldosteronism (hypertension and hypokalemia) but do not exhibit the expected increase in plasma aldosterone to plasma renin ratio. Patients with pseudohyperaldosteronism have low levels of both aldosterone and renin.

Table 6. Mechanisms underlying the various causes of pseudohyperaldosteronism

| Condition | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Liddle’s syndrome | A gain-of-function mutation of the gene encoding the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium chloride transporter. |

| Gordon syndrome | A gain of function mutation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride co-transporter in the distal nephron. Unlike other causes of pseudohyperaldosteronism, Gordon Syndrome is associated with hyperkalemia instead of hypokalemia. |

| Defects in adrenal steroidogenesis | Deficiency of 11beta-hydroxylase enzyme results in a build-up of 11-Deoxycorticosterone (which has intrinsic mineralocorticoid activity) |

| Medication-induced | Corticosteroids and contraceptives. |

| Excessive intake of licorice, grapefruits or carbenoxolone | Inhibition of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 |

| Apparent mineralocorticoid excess | An autosomal recessive condition characterized by an inactivating mutation of the 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 enzyme |

| Cushing’s syndrome | Excess cortisol binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor due to saturation of the 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 enzyme |

Pseudohypoaldosteronism

Cardiac arrest due to life-threatening hyperkalemia

Infants born with this condition present with sudden cardiac death

Cutaneous manifestations (folliculitis and atopic dermatitis)

Patients with PHA1 can present with multiple cutaneous manifestations, including folliculitis and atopic dermatitis

Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency

Hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a characteristic cutaneous sign in patients with familial glucocorticoid deficiency(FGD), which improves with treatment of FGD.

Hypoglycemia

Patients with FGD can present with recurrent hypoglycemia. Possible hypoglycemia-related seizures have been reported and can predispose patients to significant intellectual impairment. Hypoglycemia should be confirmed objectively via Whipple’s triad, i.e., biochemically confirmed hypoglycemia, hyperadrenergic or neurologic symptomatology suggestive of hypoglycemia and prompt resolution of symptoms after administration of glucose (orally or parenterally)

Pheochromocytomas And Other Paraganglioma Syndromes.

Hypertension

Clinical features

Hypertension is the most frequent physical manifestation of pheochromocytoma, accounting for a prevalence of 80-90% in this patient population. Hypertension may be either paroxysmal or sustained, although normotension may be a presenting future in a small subset of patients.

Recent evidence suggests that pheochromocytomas and paraganglioma syndromes (PPGLs) account for 0.2 to 0.6% of all hypertensive cases seen in outpatient practices.

Table 7. Review of the location and cardiac effects of catecholamines.

| Adrenergic receptor (location) | Cardiac-specific effects |

|---|---|

| α1 adrenergic receptor (smooth muscle of arteries and veins) | • Increases systemic blood pressure through vasoconstriction. • Positive inotropic effects |

| α2 adrenergic receptor (presynaptic surface of sympathetic ganglia and on smooth muscles) | Arterial vasodilation |

| β1 adrenergic receptors in cardiomyocytes | • Positive inotropic effects under direct stimulation by epinephrine and norepinephrine • Positive chronotropic effects through stimulation of the cardiac pacemaker cells • Receptors present in the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney under stimulation by catecholamines release renin leading to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis |

| β2 adrenergic receptors (smooth muscles and sympathetic ganglia) | • Vasodilation of muscular arteries. • Induces increased norepinephrine release from sympathetic ganglia |

| D1 dopaminergic receptor (kidney vasculature) | Stimulation results in vasodilation of renal arteries |

| D2 dopaminergic receptor (presynaptic) | Negative inotropic effect by inhibiting norepinephrine secretion from sympathetic nerve terminals |

At high concentrations of dopamine, as might occur with PPGLs, dopamine stimulates α1 and β1 adrenergic receptors, which leads to vasoconstriction and an increased heart rate, respectively.

Adapted from Zuber et al. (2011) Hypertension in Pheochromocytoma: Characteristics and Treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 40:295–311

Hypotension

Hypotension is usually an unexpected finding in patients with pheochromocytoma. Clinicians should, however, be aware of the possibility of a paradoxical decrease in blood pressure in patients with PPGLs. Interestingly there are even reports of hypotension and hypertension rarely co-existing in rapid cycling paroxysms.

Generalized hyperhidrosis

Excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis) is a classic finding in pheochromocytoma. There is no reported prevalence in patients with pheochromocytomas, although the triad of hypertension, palpitations, and hyperhidrosis has a specificity of more than 90% in clinching the diagnosis.

Cardiogenic shock

Pheochromocytomas can cause secondary Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. This classically presents with heart failure signs or even profound cardiogenic shock.

Nonclassic Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (NCCAH)

Clinical hyperandrogenism (acne and hirsutism)

NCCAH accounts for up to 2% of cases of hyperandrogenemia involving women in their reproductive years. Hirsutism, which is the growth of terminal male pattern hair, is evaluated with the modified Ferriman-Gallwey score, which happens to be a somewhat objective clinical assessment tool. There is wide variability in the prevalence of hirsutism, ranging from 1 to 33%.

The degree of hirsutism, however, does not correlate positively with circulating androgen levels due to differences in skin sensitivity to circulating androgens.

Other features of hyperandrogenemia seen in NCCAH

- Androgenic alopecia

- Anovulation

- Irregular menstruation

Testicular adrenal rest tumors

Testicular adrenal rest tumors (TARTs) typically occur in males with classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia, although it has been reported in NCCAH as well. TARTs in boys with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) are known to regress in size with optimal supplementation of hormonal insufficiencies. They are diagnosed based on clinical and radiographic findings, with biopsies being unnecessary in most cases.

Signs of insulin resistance (skin tags and acanthosis nigricans)

Insulin resistance has a significant association with NCCAH, although some authors believe this association could be secondary to glucocorticoid use in this patient population. Hyperinsulinemia mediated skin manifestations have been described elsewhere

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!